Israel – from victim to perpetrator to victim – a back and forth for 80 years – Part 1

The Middle East problem can only be understood if one knows the history and the current geopolitical situation – emotions do not help.

Peter Hanseler / René Zittlau

Introduction

It is astonishing how quickly the media and exponents, who like to see themselves as experts, have plunged into an unspeakable moral and emotional bath, only to be overtaken shortly by facts that force the same exponents to do a U-turn. In some cases, this has already happened.

Many of our readers asked why we hadn’t written earlier about the big event, about the bloodbath that leaves no one cold. It was clear who the culprits were.

We took the time to research and reflect extensively before we took up the pen, a privilege that news media do not have.

We do not see it as our task to take sides and condemn exponents, but to sort out and analyze the facts and thus create a basis for a discussion that could show a way out, even if – as is so often the case – it is not taken.

Analyses that ignore the historical facts which have led to the current situation fall short. Unfortunately, this applies to most of them.

The uniformity of the points of view represented in the Western media and on the stages of Western politics is not only the result of political calculation or ingrained values, it is a clear indication of a lack of understanding of the complexity of the matter.

We are aware of this, which is why René Zittlau and I decided to write this article together – too many facts had to be examined in order to provide our readers with an overview within a sensible period of time.

This article is the first in a series. We regularly commence our series with a historical review. And so our reflections begin with the First World War, as there was peace between the Arabs and Jews until 1917. It will come as no surprise to any of our readers that it took the emergence of the Empire at that time to create discord among peoples.

World War I – the seeds of the Palestinian conflict are sown

The First World War is characterized by several peculiarities that are often overlooked. This is despite the fact that they have many parallels with the current situation that are worth mentioning.

Firstly, the later opponents of the war stumbled like sleepwalkers into a global bloodbath that initially presented itself as a family feud. The German Kaiser (Wilhelm II), the Russian Tsar (Nicholas II) and the British King (George V) were all related (cousins), and through ego and naivety caused a conflict that within weeks developed into the greatest bloodbath of mankind up to that point – with the active assistance of the French.

The parallels in today’s geopolitical situation to 1914 are discernible: a local conflict that, due to alliances, ill-considered statements and actions, has the potential to once again slide out of the control of the powerful. The previous Middle East conflicts were all local – the current one is anything but.

Secondly, this first global conflict subsequently led to the fall of three giant empires: The Ottoman, the Austro-Hungarian and the Russian. The world map looked different after that.

If the current conflict also escalates into a world war, the map of our planet will be unrecognizable afterwards. Never before have the underdogs been so strong and connected at the time when the hegemon was contemplating a liberation strike.

Thirdly, the victorious French and British, with the active assistance of the coming hegemon, not only laid the foundations for the Second World War through their behavior after the war with the Treaty of Versailles, but – driven by greed for power and money – began right in the middle of the war to plant the seeds for the Palestinian conflict that has been raging for 80 years.

Greed for money is also rampant in today’s conflicts. The parallels with 1916 are astonishing. Not countries, but financial giants, financially much more powerful than countries, are already in the process of securing Ukraine’s prime assets. The biggest body snatcher is BlackRock. Even the seemingly worthless Gaza Strip has a fabulous treasure in the form of natural gas off its coast. We will also take a closer look at and classify this fact, which is not widely known to the general public.

The First World War is therefore the ideal starting point for our journey through time.

1916 – The Sykes-Picot Agreement

Not even half of the four-year war (August 1914 to November 1918) had passed when the two eventual victorious powers, Great Britain and France, were already setting about dividing up the spoils of war in the Orient.

On May 16, 1916, a secret agreement was concluded between Great Britain and France on how the colonies of the Ottoman Empire could be divided up in the most advantageous way for these two powers. It goes without saying that the interests of France and Great Britain were at the center of this agreement and not the interests of the peoples of the countries concerned.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement bears the name of its authors. Mark Sykes was a British military man, traveler, member of the House of Commons and Conservative political advisor to the British leaders on Middle East issues. He was influential and was also involved in the Balfour Declaration to be discussed below. François Georges-Picot, was a French diplomat and lawyer who wanted to increase French influence in the Middle East. Incidentally, he was the great-uncle of the later French President Giscard d’Estaing.

A glance at the following map shows just how much a capable diplomat could influence the course of history. The French negotiator Picot was astoundingly able to achieve a result that in no way corresponded to France’s real position of power in 1916, having lost its position as a world power over 100 years earlier.

The agreement correctly anticipated the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire as a result of the First World War and the depiction comes close to the divisions of the Middle East that took place after the end of the war.

1917 – Die Balfour Declaration

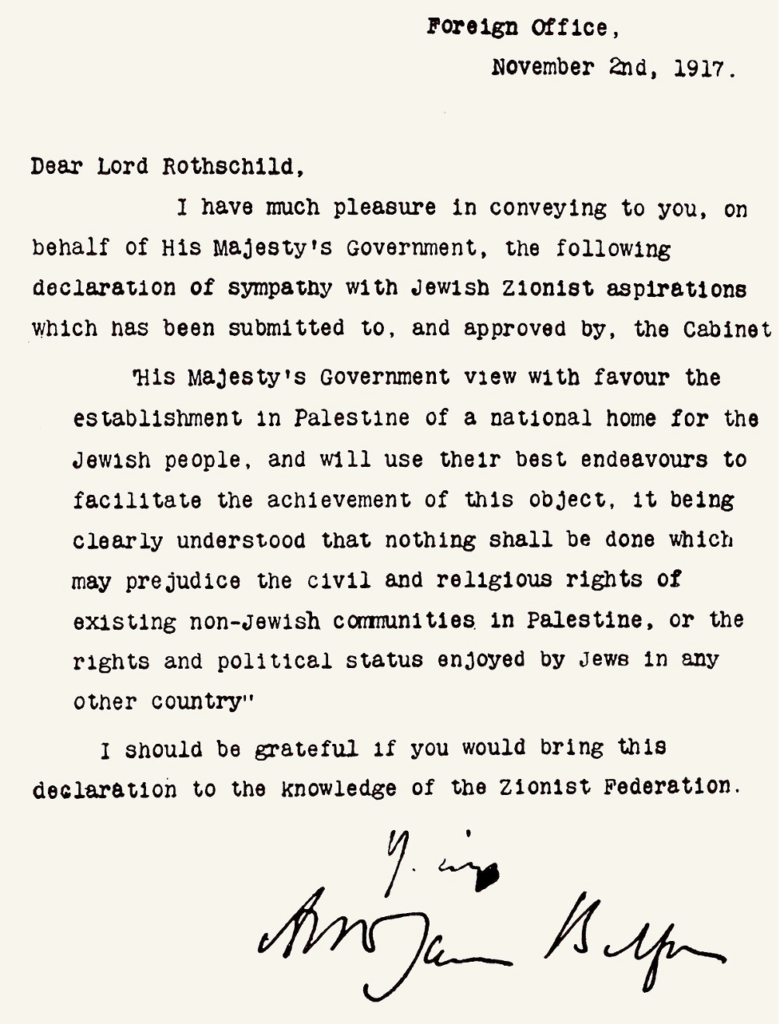

This world-famous letter from Arthur Balfour, the British Foreign Secretary, to Baron Walter Rothschild is interesting from several points of view.

The text suggests that the British were concerned with providing the Jews, represented by the World Zionist Organization, with a homeland (not a state) in Palestine, so that the Jews scattered all over the world would have a home. This seemed like noble behavior on the part of the world power Great Britain.

The copy of the declaration shown above is the only version that has survived the test of time. There are scholars who assume that the British drew up different versions and gave one – the one shown above – to the Jews and another to the Arabs, and that the two were in no way identical.

The aim of the British was to establish themselves as the guarantors of the Jewish homeland in Palestine. Palestine lay between British-controlled Egypt with the geopolitically decisive Suez Canal and Mesopotamia (today’s Iraq), which the British wanted to incorporate after the war and did so.

The British wanted Iraq because of its oil and also Palestine, so that no other power should be able to come between Iraq and Egypt. Peter Haisenko, England, the Germans, the Jews and the 20th century.

So the British were not at all interested in helping the Jews. Rather, they sought to maintain a Palestine that was favourably inclined towards the world power. Palestine had no raw materials of its own. This plan provided efficient protection for the Iraq-Egypt land bridge. As always, what was said by a world power had nothing to do with reality, but was merely a building block for a larger geopolitical goal.

April 1920 – Sanremo Conference

The First World War ended in November 1918, and the biggest loser was not the German Empire. The big loser was the Ottoman Empire. It went under.

The League of Nations was founded on January 10, 1920. On its behalf, the Sanremo Conference was held in April of the same year.

The spoils of war were now officially divided up there, after the French and British had already reached an agreement in principle four years earlier in the Sykes-Picot Agreement.

The British, who still functioned as a world power, albeit already weakened, took what they had always wanted. In addition to Palestine, which consisted of the territory of present-day Israel and Transjordan (today’s Kingdom of Jordan), the British were given Iraq.

The French received Syria and Lebanon.

The countries awarded to the parties were referred to as “mandated territories”. The aim was obviously to give the world the impression that the British and French would support these countries in their respective interests. However, these were simply countries that the two had seized as colonies, including a completely free border demarcation agreed by treaty. Obviously, in 1920, diplomacy was already dominated by the kind of political correctness that rapes language in order to conceal evil deeds.

The Middle East thus became largely British. The British invaded Palestine from Egypt via Gaza. They managed to annex Egypt, Sudan, Palestine, Iraq and practically the Arabian Peninsula from the former Ottoman Empire. They wanted Egypt because of the Suez Canal, Iraq because of the oil and with Palestine they controlled the land connection between the two and thus also brought Saudi Arabia under their at least indirect control in passing. At that time, nobody was interested in Saudi Arabia because it was poor and no oil had yet been found. This only happened in 1938.

In the following, we will only be focusing on the British Mandate of Palestine.

August 1920 – The Treaty of Sèvres

After the Treaty of Sanremo, the Treaty of Sèvres, literally “THE TREATY OF PEACE BETWEEN THE ALLIED AND ASSOCIATED POWERS AND TURKEY”, signed on August 10, 1920, formally ended the First World War.

It regulated in detail what concessions Turkey had to make as the successor to the Ottoman Empire.

At this point, we are only interested in the regulations that were of significance for further developments in Palestine and the later Israel.

Article 95 (full text here) regulated the fate of Palestine and also referred to the Balfour Declaration, without mentioning it by name.

«[…] The Mandatory will be responsible for putting into effect the declaration originally made on November 2, 1917 [Balfour Declaration], by the British Government, and adopted by the other Allied Powers, in favour of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine […]»

ARt. 95 Vertrag von Sèvres

Article 95 stated that the Balfour Declaration would be adopted. However, the wording goes beyond this in terms of content. If the Jews were only promised a homeland in 1917, Article 95 speaks of a “national home”.

It is important for further analysis that Article 95 states unequivocally that the non-Jewish population should enjoy all civil and religious rights and should not suffer any disadvantage from the fact that Palestine becomes the homeland of the Jewish population.

1922 – Mandate agreement on Palestine

The Sanremo agreements on the British League of Nations Mandate of Palestine were ratified in a separate agreement in 1922. This also named an unspecified Jewish Agency as a partner for the implementation of the mandate.

The Jewish Agency, which was founded in 1929, is still a very influential Zionist organization today. An NGO, as we would say today. Its predecessor, the Palestine Jewish Bureau, was founded in Palestine in 1908 by the World Zionist Organization. Its task was to represent the interests of the Jews vis-à-vis the Turkish authorities, support immigration to Palestine and promote the acquisition of land.

In the document in which the League of Nations grants Great Britain the mandate over Palestine with reference to the Treaty of Sanremo, Article 4 – which can be viewed here – refers in part verbatim to the actually non-binding Balfour Declaration of the British government to Lord Walter Rothschild.

1920 to 1948 – Immigration to Palestine

Introduction

Although the British government had made a non-binding commitment in 1917 with the Balfour Declaration to promote the creation of a Jewish “homeland”, the Sanremo and Sévres Treaties raised this non-binding commitment to a legally binding level. This raised the question of how Jewish immigration should be organized.

Unproblematic from 1920 to 1933

The British administration, in cooperation with the Jewish Agency, established the following procedure:

Twice a year, the colonial authorities set immigration quotas based on the current economic and social conditions in Palestine. The Jewish Agency created a Palestine Office in Jaffa, which was responsible for the organizational handling of immigration. In the respective countries of emigration, there were local Palestine offices subordinate to the Palestine Office in Jaffa, which issued immigration certificates to those wishing to emigrate within the framework of the specified quotas. These were submitted to the respective British consulates for final approval. This enabled the British administration to regulate the immigration quotas. Until the early 1930s, the supply and demand for immigration certificates was balanced, so that there were hardly any problems.

Hitler also causes problems in Palestine

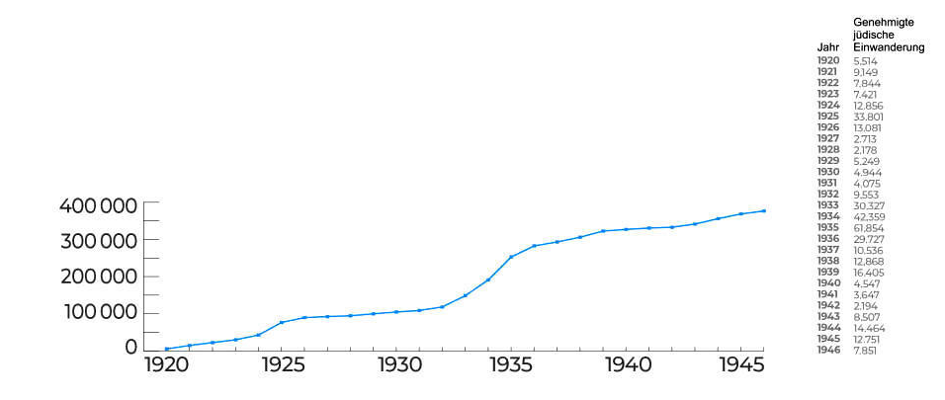

This changed with Hitler’s rise to power in January 1933, when demand in Germany immediately reached unimagined heights. This type of organization gave the Jewish Agency, via the Palestine offices, considerable opportunities to control immigration according to its own criteria, which it did.

“The Central Office for the Settlement of German Jews within the Jewish Agency for Palestine, formed in 1933, excluded anti-Zionists as certificate applicants; young, healthy people with some training in agriculture or a trade were preferred as candidates for aliyah [immigration], as well as people with some capital; the needs and interests of Palestine took precedence over the rescue of Jews’, at least until 1938.”

Alexander Schölch, “Das Dritte Reich, die Zionistische Bewegung und der Palästina-Konflikt, 655

Conflicts in the coexistence of Jews and Arabs

The moderate immigration in the 1920s hardly led to any conflicts between the different cultures. On the contrary. The Arab majority welcomed it and hoped it would lead to an economic upturn.

Nevertheless, there were also armed clashes between the Arab population and the colonial power. The reason for this was the rejection of the release of Palestine into independence.

Between 1936 and 1939, there was another major armed Arab uprising. This was triggered by the sharp rise in Jewish immigration and renewed demands for independence. While 80,000 Jews came to Palestine between 1924 and 1931, this figure rose to around 200,000 between 1932 and 1939, mainly as a result of the political changes in Europe. (Source: Federal Agency for Civic Education)

According to Wikipedia, the British administration deployed 20,000 soldiers to suppress the uprising. It also armed thousands of Jews as auxiliary policemen and Arabs loyal to the colonial administration. As a result, there were thousands of deaths on both the Arab and Jewish sides.

1939 – White Paper

In the White Paper of May 1939, the British government drew conclusions. It announced:

“The objective of His Majesty’s Government is the establishment within 10 years […] The independent State should be one in which Arabs and Jews share government in such a way as to ensure that the essential interests of each community are safeguarded.”

White papaer 1939

The Jews must have perceived the measures as a defeat. But the Arab leaders did not support this new policy either, as the White Paper rejected the demand for immediate independence. All these measures contradicted previous policy, the Mandate Treaty and thus the Balfour Declaration.

Nevertheless, the 1939 White Paper determined British policy until 1947, when the political process for the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 began.

This included circumventing the immigration quotas for Jews to Palestine set by the British administration. Between 1934 and 1948, an additional 150,000 Jews came to Palestine illegally. The Jewish Agency also concluded an agreement with the German government under which 50,000 German Jews were allowed to emigrate to Palestine.

As it turned out, these were not good conditions for the long-term peaceful coexistence of native Arabs and Jewish immigrants.

1920-1948 – Immigration maps and data

1917

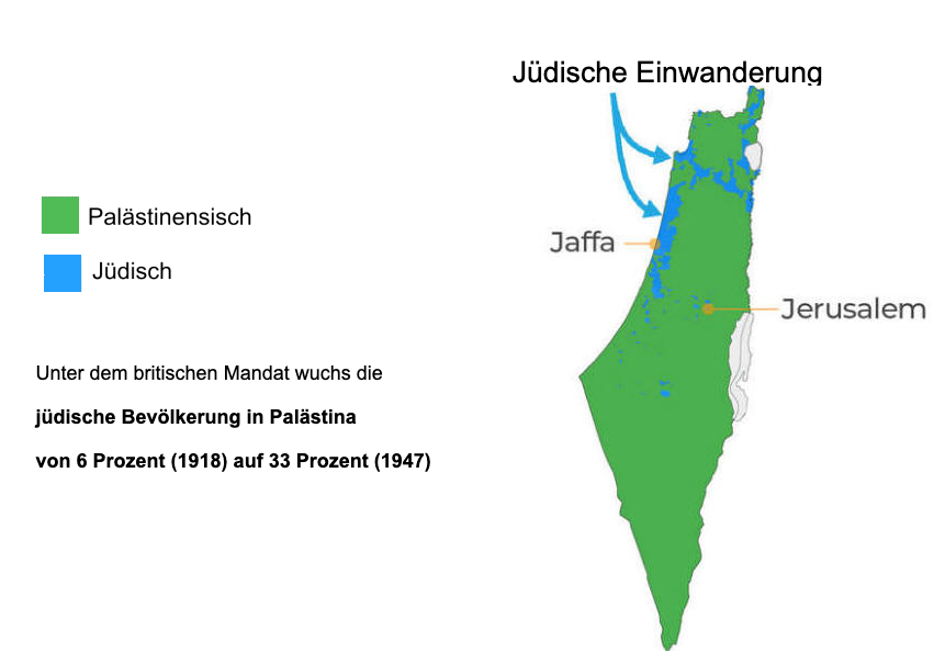

Translation: Green: Palestinian; Blue: Jewish:

On October 31, 1917, British forces conquered Palestine from the Ottoman Turks to end 1400 years of Islamic rule over the region.

In 1920, their 28 years of British Mandate rule over Palestine began. Before the British Mandate in Palestine, Jews made up about six percent of the total population.

1947

Translation: Under British Mandate rule, the proportion of the Jewish population rose from 6 percent (1918) to 33 percent (1947).

1920-1947 – Grafik der Zuwanderung

The influx of Jews increased noticeably once again after the National Socialists came to power in Germany.

1947 – UN Resolution 181 – two-state solution

After the Second World War, it became apparent that the British wanted to get rid of the mandate over Palestine, as the rules they had drawn up themselves in the White Paper led to problems with both the Jews and the Arabs. Although Great Britain was one of the victors of the Second World War, it had to hand over the sceptre of world domination to the USA and had huge economic problems.

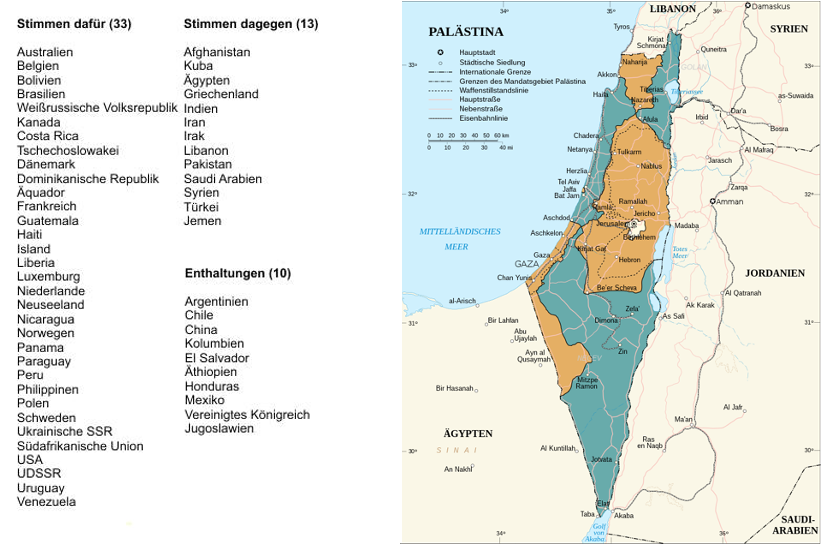

The UN, created in 1945, took up the problem. It set up a commission to draw up proposals on how the problem of the Arab majority and the Jewish minority could be solved. Two options were worked out. One was a one-state solution and the other was a plan for the creation of a Jewish and a Palestinian state – the two-state solution that is still being discussed today.

With Resolution 181 (original document here), the two-state solution was finally adopted by a majority.

However, the Arab UN members unanimously rejected the plan. Not only did they reject a Jewish state, they also saw the plan as a violation of the rights of the Palestinian majority population.

For their part, the supporters of the plan exerted great pressure on the UN to accept the plan, above all the Jewish Agency, which was now active worldwide.

There were also Jews who rejected the plan because it did not go far enough for them. In the end, the following partition of the land was accepted with Resolution 181, whereby Jerusalem was given international status:

The British mandate ended on May 14, 1948, and one day later, on May 15, 1948, the State of Israel was proclaimed.

Despite Resolution 181, which explicitly called for the establishment of a sovereign Palestinian state, this part of the resolution, which was binding under international law, has not been implemented to this day.

Conclusion

In this first part, we have worked out the following:

Palestine, which comprised the present-day states of Israel and Jordan as well as the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, came under British administration with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in 1920, as planned in the secret Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916.

From 1917, during the period of the British Mandate, there was strong Jewish immigration to Palestine, which was accelerated by the persecution of Jews from 1933.

The settlement behaviour of the Jews was often characterized by ruthlessness and violence towards the Palestinian population, which was tolerated by the British administration. Due to this and the sheer mass of Jewish immigrants, there were repeated armed riots and uprisings.

After the Second World War, a two-state solution was brought about by the UN, as the problems that had arisen could no longer be managed otherwise. As a result, the Jewish minority was awarded 56.47% of the Mandate territory (excluding Transjordan). This area essentially corresponded to the territories that the Jewish settlers had acquired in the course of their immigration. Until the partition, however, there was no Jewish majority there.

David Ben Gurion, however, did not care about UN Resolution 181 and took the end of the British Mandate on May 14, 1948 as an opportunity to proclaim Israel as a state the following day. This contradicted the two-state solution imposed by the UN.

The state of Israel entered the world stage and at the same time, the historical Palestine ceased to exist.

Outlook for part 2

In the second part of our series, we will discuss the very bloody events from the founding of Israel until October 7, 2023, and then examine them geopolitically in part 3.

16 thoughts on “Israel – from victim to perpetrator to victim – a back and forth for 80 years – Part 1”